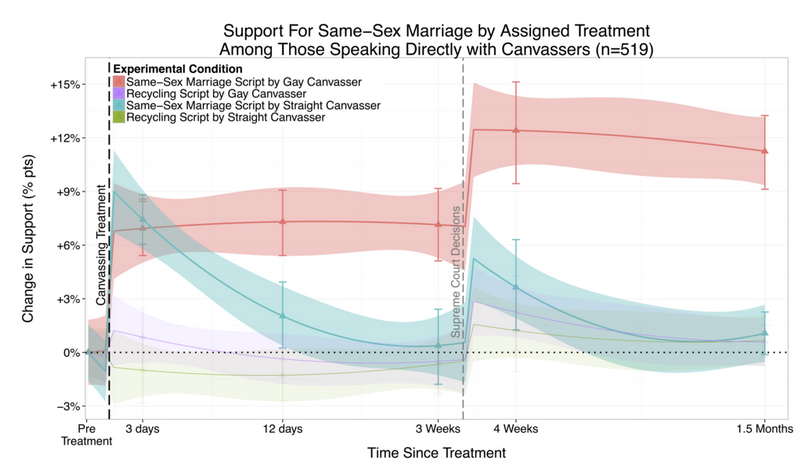

A chart from LaCour and Green’s study of voter attitudes before and after they spoke with either a gay or straight canvasser about their views on same-sex marriage. These data are now disputed. (Source: Mike LaCour’s web site, accessed May 27, 2015.)

By Michael Kuczkowski

“… just because the data don’t exist to demonstrate the effectiveness of this method of changing minds, doesn’t mean the hypothesis is false.”

This sounds like a weird riff on a famous line from Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. But, this isn’t a parody, and it’s not really funny.

The quote is from Columbia University Prof. Donald P. Green, a leading political scientist. He said it while talking to This American Life last week, after revelations that a widely heralded Science magazine article he co-authored with a graduate student from the University of California at Los Angeles may have been based on data fabricated by that graduate student.

If you read our blog, you probably know about the study. In it, gay canvassers spoke to Los Angeles voters who opposed same-sex marriage, asking them about their attitudes on the issue. After a single 20-minute conversation with the canvasser, who revealed his or her sexual orientation in the process, those voters who initially reported being against same-sex marriage said they now supported it. A year later, according to the study, they still did.

The study was a national sensation. The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal wrote about it. This American Life devoted an entire episode to the study, and has now posted blogs (here and here) explaining what went wrong.

Last week, Professor Green sent a letter to Science asking that they retract the article; the publisher says the issue is under review. Michael J. LaCour, the graduate student in question, stands by his study, so far. His position appears shaky. He says he will issue single, definitive response by Friday, May 29.

Here’s what happened, according to news reports and a review of a critique of the study published online by a pair of researchers at Berkeley: Those researchers – graduate students Joshua Kalla and David Broockman – were intrigued by LaCour’s results. They tried to duplicate his research methods in a follow-up study, and they failed.

The more questions they asked, the more the study began to collapse like a house of cards. Confronted by his graduate advisor at UCLA, LaCour admitted that he lied about a significant amount of grant money that he claimed he was using to pay research participants. He changed his story about the incentives he used, saying that instead of paying participants $5 per person, he offered them a chance to win an iPad. Then he said he’d accidentally deleted his data set, which had been publicly available (and was accessed by Kalla and Broockman).

Meanwhile, as Kalla and Broockman dug in further, they found a number of statistical anomalies. LaCour’s data seemed almost identical to data from a 2012 national data set – even though his data set was of Los Angeles voters (hardly reflective of the nation). Lacour said he used a kind of sampling technique that would be highly unlikely to replicate any other data set, so the patterns didn’t make sense. His data were too perfect, replicating the other study’s distribution patterns and showing no outliers typical of large-scale quantitative research.

Suddenly the remarkable results seemed remarkable for an entirely different reason: A far-reaching allegation of fraud.

The questions about the study call into question a number of issues about academic research, graduate student supervision, peer-reviewed publications and mainstream reporting. And, they may well cost LaCour his job (he’d recently been appointed to a teaching post at Princeton.)

But, those are not really our concerns. We’re communicators. We want to know, is the science wrong? (And, on a more personal level, was my blog post last month wrong?)

The answer to those questions would appear to be no. But it requires some explaining.

Let’s say, as seems likely, that the piece by LaCour and Green is a fiction. If so, that means LaCour went to tremendous lengths to create a fictional data cohort that created the appearance of a credible study. He duped some pretty impressive folks and sent hundreds of canvassers out on what appears to have been a wild goose chase.

But, some elements of the study were real. The Los Angeles LGBT Center canvassers did go out and interview real Los Angeles voters. The audio clips of interviews that aired in This American Life were also real. And, some of the people, as interviewed, did change their minds as a result of that outreach, at least in the short term.

The statistical correlation between the sexual orientation of the canvassers and the degree and robustness of mind change appears to be completely fabricated. We also don’t know if people’s minds remained changed after that initial conversation.

But, the technique the canvassers used, which is what I focused on in my blog post, was not discredited. We don’t have any data to say whether it was effective or not. Which is a shame. As Green told TAL: “All that effort that went in to confecting the data, you could’ve gotten the data.” But they didn’t.

So what do we know about changing minds?

As the original TAL show said, it’s rare. Hard to predict, harder to control. The research we have on changing minds touches on myriad disparate fields, including mass communications, political science, cognitive behavior, economics, psychology, neuroscience, social networks, linguistics and sociology. There’s no silver bullet, but there are some important patterns.

Here are three sources that provide credible guidance on the subject:

Howard Gardner’s 2004 book Changing Minds offers up insights on what causes people to change their minds in different circumstances and contexts. Gardner, a Harvard psychologist, highlights 7 “R’s” that are relevant to the process of changing minds: reason, research, resonance, representative redescriptions, rewards, real-world events and resistances (that must be overcome). He also highlights how different the process of changing minds is in different contexts: large-scale heterogenous groups versus large-scale homogenous groups; change inspired by art or science; formal, instructional mind change, such as schools; small groups or families; and one’s own mind. These distinct realms call for different approaches.

John Kotter has been talking about change within organizations for decades. His book Leading Change, outlines an eight-step process for leading change, aimed at organizational leaders. While his process is focused on organizational change, communications plays a vital role in most steps. (Interestingly, Kotter’s model is built on his analysis failed organizational change efforts, rather than successful ones.)

Finally, this year the Institute for Public Relations recently launched a Behavioral Communications research program, led by Dr. Terence Flynn and Ogilvy’s Christopher Graves, to examine the role of communications in driving behavioral and attitude change. The results of that team’s extensive literature review are consistent with many of the precepts we’ve touted here: the messenger matters; emotional messages trump analytical ones; the “backfire effect” (in which people harden their beliefs in the face of contrary evidence) is real; and narratives are powerful vehicles for persuasion.

Flynn presented a draft of their model for changing minds at a conference I attended in January, and I think it’s very interesting. Watch that space, I’m a believer in their science.

(Source: Pew Forum)

As for the issue of same-sex marriage, we know that Americans have, in fact, changed their minds. Polls by the Pew Research Center for Religion & Public Life, for example, show that 52 percent of Americans support same-sex marriage today, up from 35 percent in 2001.

What we don’t have is a large-scale experimental design study that tests the theories above in a “live” environment, which would be great to have, without question.

What’s interesting about this is that LaCour may well benefit from a kind of reverse “backfire effect.” LaCour’s study was really a narrative focused on the connection between the sexual orientation of the canvassers and the lasting effects of changed minds. Same-sex marriage is, for many people, an emotional and deeply personal issue. It all adds up to a remarkable story, even if the data were bogus.

I wonder if, as with the discredited research on a link between autism and vaccines, people who initially found the study compelling will forget it was discredited and continue to believe that gay canvassers were able to change minds in a real and lasting manner.

Still, something about it seemed too easy. It suggested an arms race of mind-changing outreach campaigns: If only we could mobilize the representatives of a disenfranchised group to engage those who supported oppressive policies, we could change the world. Then again, so could our opponents.

Meanwhile, we’ll continue to focus on the tools and techniques we know work: credible messengers, strong narratives, emotional connections and an awareness of the environment. It’s not easy, but it’s what makes for very interesting work.